RX&SLAG Paris is pleased to present Pascal Convert's second solo exhibition, just one year after "The Voices That Fell Silent." Today, he brings together 14 works – including 8 created specifically for the occasion – to speak to us about current events by turning to the stars, the constellations, to listen to the faint rumble of the world. In doing so, he takes a step back and a certain distance from the streams of information that obscure the understanding of ongoing conflicts. He blends different dimensions (temporal, symbolic, and poetic) through techniques, materials, the importance of color, and his reflection to "rebirth things and address the question of what survives and what leaves a human trace."

Shifting the focus

From dramas to faults, to scars. Pascal Convert directs his gaze towards events that impose themselves as cataclysms in the lives of individuals confronted with a madness inseparable from human history. But unlike Goya, who portrayed it directly and starkly in the series of prints "The Disasters of War" (made between 1810 and 1815), Pascal Convert zooms out and shifts the focus. He creates works in which time seems suspended, halted at a moment in history (e.g., "Stumps of Verdun crystallized") or dedicated to a memory (e.g., "Anna Politkovskaya," "Bark of Stone," "The Voices That Fell Silent #2"). Like an alchemist, the artist transmutes the horrors of conflicts into poetic works that invite us to take time for questions and reflection, far from the pitfalls of passionate reactions.

Which constellations?

The title of the exhibition refers to a book Pascal Convert published in 2013 with Grasset, "La Constellation du lion," in which he recounts his childhood, his mother "surrounded by anxiety and in the shadow of a father" who was a great resistance fighter, but also the betrayals and deaths. "With the exhibition, we move from this constellation where the familial and a slice of history intertwine to a constellation in which hyper-current events and a landscape more complex than the mere literality of current journalism intertwine," he points out. Art becomes a filter that operates through distillation, and the artist, the inventor of a new language. "In these works, I pose the question of imagination, Susan Sontag's question: how to imagine the pain of others? Where do we position ourselves to imagine? Close by? Do we understand better? Can we imagine from afar? All of this may seem cryptic, but I wanted an exhibition that is in a polysemic actuality."

Palimpsest materials

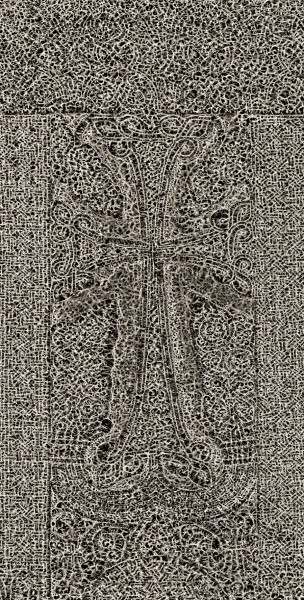

In this new exhibition, Pascal Convert becomes an archaeologist of memory and superimposes temporalities. Indeed, he reuses glass plates produced between the 1930s and 1970s, like ready-mades on which he intervenes. They become palimpsests and become laden with meaning. He engraves "the monitoring of the last heartbeat of a person" (Pan #2) – on a slab of azure blue Cirey – or of a newborn child (Pan #3) – on a slab of red Boussois. On this latter one, a date is inscribed: April 15, 2019. He won't say more, it's up to each individual to figure out what it corresponds to. In "The Jordan," the biblical river transforms into a scar that crosses the marmorite plate, a black opal glass long used as a tombstone but whose production has ceased. "This river, which separates this interlocking of territories from Lebanon to the Dead Sea through Israel and the West Bank, has become a stream of blood." In "Constellations," he places 13 crystal-blown bells on large cobalt plates, each covering a shard of yellow uranium glass, containing a very low level of uranium. The combination of colors inevitably evokes the Ukrainian flag... The trace remains present with the imprints obtained by graphite rubbing on khachkars from the Djoulfa cemetery (Bark of Stone), these symbolic steles of Armenian culture destroyed by Azerbaijani soldiers. A conflict that leaves the international community indifferent. "I try to create shapes that think, that give us time," he concludes.

Interview with Pascal Convert for RX&SLAG Paris,

exhibition "Constellations", from May 3rd to June 8th, 2024

Could you shed some light on the title of the exhibition at the RX&SLAG gallery, "Constellations"?

This title comes from "La Constellation du lion," published by Grasset in 2013, an autobiographical book in which I talk about my mother's depression, my childhood, her father who was a great resistant, betrayals, and deaths. With the exhibition, we move from one of these constellations where the familial and a slice of history intersect to a constellation in which hyperactuality and a landscape more complex than the mere literalness of current affairs journalism intertwine. I find that the period is very complicated to understand and analyze because we have never been in such a chaotic situation in terms of information, so I put myself in a position of observing the constellations and stars around us to try to understand what is happening on Earth.

Is the choice of black and white for the photographs a way to create distance or to speak about time?

I used it for the photographs of Afghanistan and Armenia because color creates a presence of actuality. These works are made with hybrid techniques, both very ancient and very contemporary, as if I were using the Hubble telescope and the "Great Telescope" of Meudon. I combine aerial photogrammetry from the Iconem company with platinum-palladium printing, which harks back to the 19th century and gives a slightly yellow tint and a certain warmth, opposite to the coldness of black and white printing. In this exhibition in particular, the materials are indicators of time, whether it's platinum-palladium or glass plates dating from the 1930s to 1970s. Among these, there are large cobalt Schott plates on which thirteen blown crystal bells are placed, enclosing a glass pebble of a very particular yellow (Les voix qui se sont tues #2). These are fragments of uranium yellow, a material containing a very low percentage of radiation. Some of the glass plates have defects, accidents that carry a temporality and the trace of the human hand.

How do you translate this connection with current events into the artworks?

People will see pieces that they will directly associate with current events, whether it's the assassination of Anna Politkovskaya or Armenia, especially the destruction of the three thousand khatchars from the Christian cemetery of Djoulfa between 2002 and 2006 by Azerbaijani authorities, but more generally, the current exodus of these populations and the lack of interest from politicians and people in this tragedy. I am not Armenian, but I am touched because it is the first Christian country. I am neither a believer nor an atheist, but what interests me is spirituality. Then, other pieces are related to hyperactuality like The Jordan River. This river, which separates this interlocking territory from Lebanon to the Dead Sea passing through Israel and the West Bank, has become a stream of blood. In these works, I pose the question of imagination, Susan Sontag's question: how to imagine the pain of others. Where do we place ourselves to imagine? Close? Do we understand better? Can we imagine while being far away? All this may seem cryptic, but I wanted an exhibition that is in a polysemic actuality.

Can some events touch and concern us depending on our physical proximity?

You can be touched by a comet passing in the sky as well as by an event that happens near you, it depends on its brightness and duration of existence. There is also the question of appropriation that has been asked of me regarding Armenia and Afghanistan: since I am neither Armenian nor Afghan, I would not have the legitimacy to appropriate this memory and human suffering, yet I do, they are shared. It's a difficult exhibition for me, I don't hide it from you. The contexts it evokes, directly or indirectly, are painful. But it allowed me to launch tracks for the future. The ancient glasses on which I engrave the inscription of the time of birth, death, or tragedy reconnect with the practice of the line, of cutting, that I used in many wall drawings or in glass engravings. The line opens times.

Could you point out some works created for the exhibition?

There are two major pieces, Les voix qui se sont tues #2 and the Pan series that echoes it. They can be the last beat of the heart or the first breath of a newborn. I called them Pan in reference to Fra Angelico: Dissemblance et figuration by Georges Didi-Huberman. On the first one, Pan #2, you can see the traces of refractory bricks on which it was cast, and on the back, the glass is, on the contrary, of a totally smooth Marian blue. On this 1.42-meter-long strip, the monitoring of the last heartbeats of a person who has just died has been engraved. The other piece engraved on a Boussois red plate, Pan #3, is one of birth. There is just one date: April 15, 2019. People will have to question the signs that I leave like when you look at a shooting star. These pieces are between life and death, as in conflicts.

Regarding colors, you mentioned the Marian blue of cobalt, the uranium yellow, and the brick red of the Boussois slab. These are colors found in classical painting. Can a connection be made?

The reference to painting is indeed present; it's also one of my exhibitions where color is also present and equally dialectical. The blue panel will be facing the red slab, and the uranium yellow on cobalt blue slabs. These are very pure colors like in classical paintings. The relationship with painting is very important to me, even though after starting with painting when I was very young, I quickly stopped to focus on glass, which was the embodiment of another medium that allowed painting differently. Glass becomes the painting itself. The link to establish is rather with stained glass windows and medieval manuscripts from the 10th and 11th centuries.

In this interplay between very recent current events and older history, is it a way to point to something universal?

It's a way to point out a difficulty in shaping thought in a period of hyper-actuality. Therefore, one must step back, create distance, and have a complex approach to support ambiguity in a time when everything becomes more authoritarian day by day. My artistic practice aims to revive things and address the question of what survives and what makes a human trace. There are moments, like currently in the courtyard of honor of the Bullukian Foundation in Lyon, where the intervention is very direct and spectacular, and others like for this exhibition, which are more marked by an inner search. I try to create forms that think, that give us time.

Is it also an opportunity to rethink the individual within a collective destiny?

I think we tend towards hyper-individualization, largely linked to the use of social networks and digital tools, and at the same time, as Bernard Stiegler analyzes, we have a loss of the individual. Everyone is a hero, and everyone is powerless. However, it's a matter of perspective. By looking at the constellations, we relativize our own position. We must try to speak about the world in a different language, like poets.