RX&SLAG is pleased to present, in collaboration with Father Yves Trocheris, the parish priest of Saint-Eustache in Paris, the preparatory drawings of the Stations of the Cross that Vincent Gicquel painted for the church of Trévérien (Ille-et-Vilaine) in 2022. The project, commissioned by François Pinault for his hometown, consists of 14 canvases for each of the stations of this Stations of the Cross. The genesis of the project can be traced through the watercolors presented today at Saint-Eustache. An intimate and unprecedented project for the artist, which could only be unveiled in a church and outside of the gallery.

"Would you feel capable of creating a Stations of the Cross?" It was with these words from François Pinault that the adventure began. It was in 2021: the Bourse du Commerce had just opened its doors, and the collector was curious about the latest works created by Vincent Gicquel in Berlin. Gicquel recalls, "In the series I presented to him, there was a character carrying another. The painting was called 'Souffler' ('To Blow'), and the connection was quite clear to him." One can applaud the collector's intuition because, knowing Vincent Gicquel's universe, it's hard to imagine that his characters could be the actors of this tragic and highly symbolic episode of the New Testament. But as he explains, "My work has always focused on depicting the human condition, our relationship to the world, and our own lives. So painting a Stations of the Cross, which is an allegory of existence, could seem quite natural to me at first. Depicting the trials inflicted on a man condemned to a tragic fate is the whole story of my painting. So I was on familiar ground. Moreover, with a palette that would harmonize with the colorful stained glass windows of the church. I undertook this work confidently, not without recalling that a certain Yellow Christ was born, too, in Breton soil more than a century ago."

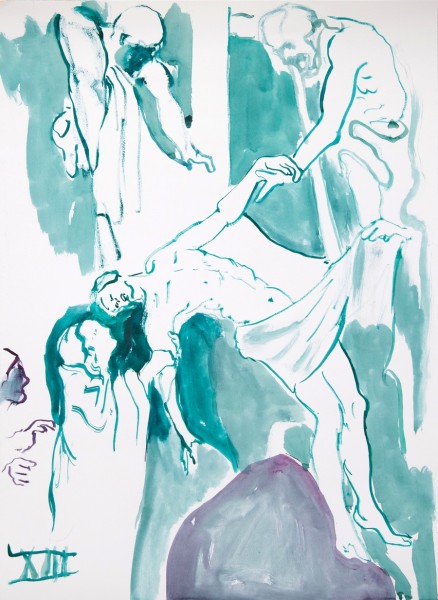

14 preparatory sketches

The research phase was long and intense, resulting in a large quantity of drawings produced over several months, as well as many destroyed. One could apply Matisse's words while he worked on the Chapel of the Rosary in Vence to explain Vincent Gicquel's state of mind, his quest, and the importance of drawings as an exploration ground: "These things must be known so well by heart that we can draw them with our eyes closed," or "I did not seek beauty, I sought truth." The 14 selected examples for this exhibition provide preparatory stages of the works for the church of Trévérien and all measure the same size—except for 2 smaller ones. Some are close to the finished work, while others are closest to the initial sketches. But all trace the narrative sequence: from the condemnation to death of Jesus to the entombment, passing through the carrying of the cross under the weight of which he falls several times, the encounter with his mother or with Saint Veronica who wipes his face, the crucifixion or the descent from the cross. The multitude of drawings produced by the artist testifies to the difficulty of approaching such a subject. "After a while, it was so complex in the face of the weight of art history that I could have given up. How could I do something unique and powerful after Caravaggio, Matisse, and all those who have made Stations of the Cross in every Catholic church?"

The right tone

The right tone had to be found. Faced with the responsibility of addressing a subject that touches on intimate and religious convictions, he had no choice but to move away from the outrageous character of his figures to incorporate a certain classicism. "I couldn't do otherwise. If I want to say 'I love you,' I'm not going to say 'blue lamp' or 'velvet,' I'm going to say the same phrase from Romeo and Juliet because you can't say things differently when they are important." The ghosts of the masters of art history flit through the lines, in a face or an attitude. If at Station 13, when Jesus is taken down from the cross, one cannot help but detect the shadow of Rubens, it is to a hallucinated Peter Doig that one thinks of at Station 2, when Jesus carries his cross, or to Simon Vouet and Delacroix when Jesus is stripped of his clothes in the 10th painting. The violence is indescribable during the crucifixion, the 11th painting. This drawing is an oxymoron, as beauty and horror merge. We discover Vincent Gicquel's art in a different light, while rediscovering his palette, with shades of transparent blues and greens. Only one drawing is entirely red, the one with Saint Veronica's veil (painting 11).

Touching the universal

Believers and curious must find a certain solemnity in those works and be touched. "Here, one cannot believe in the story if the line is not classical." And indeed, this humanity, which usually elicits a smile under Vincent Gicquel's brush, has become more serious here. It is true, fragile, full of humility, mercy, and suffering. It rises again each time, carried by a life impulse, by convictions. One can draw parallels with the artist's work in his studio, but also with the life journey of each individual. It touches the universal, and its message goes beyond any religion; it points out what makes us human. "My aim is that of hope, of being able to love oneself, to understand each other despite misunderstandings. That is true sharing."