SLAG&RX is pleased to present Twice Broken Heart, an exhibition of new works by Naomi Safran-Hon. This recent body of work marks another chapter in Safran-Hon's ongoing exploration of charged, painful, and intimate histories where the language of art provides a message of hope.

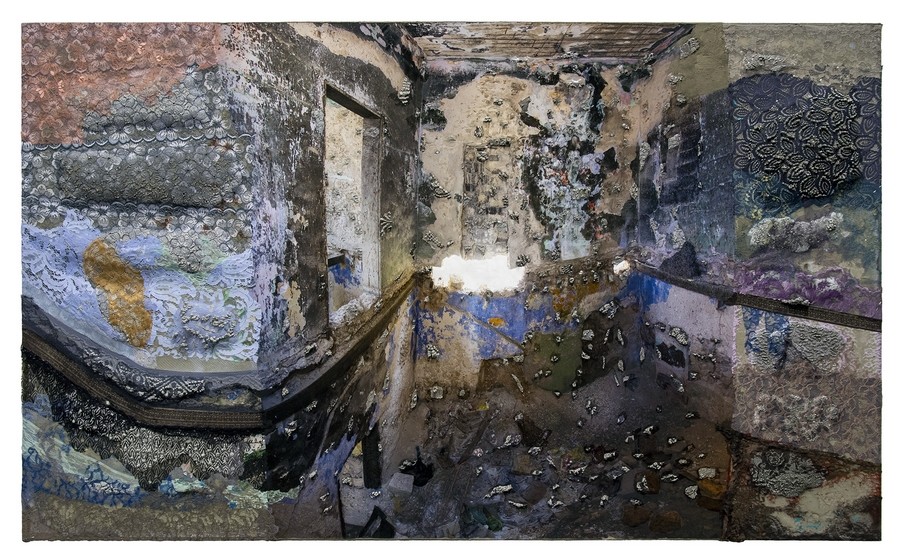

Central to this exhibition is an acknowledgment of language's profound limitations when confronting war and devastation. Words often falter and fail, and Safran-Hon's work offers a visual vocabulary for experiences that resist simple narration or explanation. She embraces seemingly competing narratives, both conceptually and within her generously layered studio process. The combination of destruction and mending evident in “River and Sea” becomes a powerful metaphor for larger stories that often exceed the boundaries of conventional discourse about conflict, displacement, and loss. Strips of lace play against graffiti and the cement bulging through ornate textile patterns appears to be growing and decomposing simultaneously. The works help liberate us to see not only an important history, but envision an imagined future.

For over 15 years, Safran-Hon has challenged and complicated the fact and fiction of the geopolitically fraught, narrow strip of land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. Her technique foregrounds architecture as the vessel for storytelling, exposing tensions and creating a viewing experience led by empathy and curiosity. Her photographs of abandoned buildings in her hometown Haifa, Israel serve as the core of her practice and reveal dilapidated houses where the original Palestinian inhabitants were not allowed to return. These buildings provide a powerful metaphor that examines what remains, what one returns to, and what the structure of a space still has to offer. She transforms these images into dimensional paintings that put in question our preconceived idea of what home is. The language of having a "twice broken heart" typically describes a relationship between individuals, yet here the intimacy and gravitation is toward this complicated place.

Following her previous exhibitions Tight Connections and All My Lovers, this new body of work pushes forward a fertile exploration of touch points and proximity. Safran-Hon's technique retains a core interest in photography as a tangible key that grounds the image in reality and space, while also introducing moments of figuration. However, her sculptural materials—cement, lace, and various textiles— increasingly claim more of the composition. The exposed seams between photographic elements and the rich application of new surfaces and depths force a double take. In “Walls for Hope in Color (two portraits),” Safran-Hon even goes so far as to feature a photographic approach on one side of the diptych, while the other serves her sculptural practice.The image shifts from two to three dimensions, playing with perception as the eye navigates undulating textures and embedded patterns, forcing the viewer to decode which elements are fact and which demand a more critical eye.

These moments of visible process are intentional and reinforce the arbitrariness of borders. She tears down and rebuilds with equal vigor, often leaving sewing pins in place or affixing paint remnants from an earlier work to layer on top of the next composition. The edges become especially important, creating a journey through material where each slice, stitch and pour leaves an impression, a mark of history.

Cement serves as a key material for Safran-Hon. It’s the fundamental building material seen in all of her architectural images, an ever-present part of each photograph. Lace, by contrast, inspires associations of family life, care, and craftsmanship. We envision the passing down of personal traditions with each soft and pliable thread. Working with objects laying flat rather than on the wall, she embraces the physicality and pressure of the cement pushing through lace. These innovative techniques and new associations embed the work with an openness to form and possibilities within the spaces.

In addition to the architectural interiors, the exhibition also features cactus paintings that introduce wider historical context. These cacti, which came to the region from Mexico in the 16th century and were used by Palestinian communities as natural fencing, serve as visual markers of destroyed Palestinian villages in the Israeli landscape. Israelis also acknowledged this plant’s importance in the landscape, calling their first generation born on the land “sabra,” the Hebrew name of the plant. Within the installation, they function as interruptions to the architectural canvases, showing nature reclaiming space—a silent testimony to histories that official narratives might overlook or inadequately address.