With its latest exhibition, RX&SLAG gallery is thrilled to announce the representation of Jean-Baptiste Boyer, a prominent figure in the resurgence of contemporary painting. Boyer now joins a roster of 25 artists collaborating with the gallery. In this solo exhibition, the young French artist, born in 1990, presents a new series titled "Un amour perdu" (A Lost Love) that spans the entire gallery, featuring some pieces specially crafted for the occasion. Across approximately twenty paintings, viewers are immersed in a realm that straddles the borders of nostalgia and melancholy, reality and fantasy, narration, and invention.

Each evocative painting, which touches the depths of sensitivity, serves as a window into the artist's state of mind—inheritant of Romanticism. Simultaneously, they stand as an ode to freedom and beauty while acting as a denunciation of all constraints, whether ideological or religious. The exhibition extends an invitation to "Follow your demons," encouraging a journey through Boyer's captivating exploration.

The Pursuit of Light

Unveiling himself, Jean-Baptiste Boyer accomplishes this with a blend of modesty and candor in his latest exhibition. Here, painting serves as both an intimate sanctuary and a realm shielding him from the chaos of the world. His emotional landscape is colored with melancholy, a sentiment further intensified by his deliberate use of a restricted color palette dominated by ochres and mineral tones. Subjects emerge from the shadows, reminiscent of the techniques employed by Caravaggio and Courbet, brought to light by the very essence Boyer tirelessly seeks. This quest for light borders on obsession for Jean-Baptiste Boyer. At times, light takes center stage, either manipulated, as seen in "Lost Love," or intensified through careful strokes that highlight elements such as a piano, a chair, a vase, or the white band of a young man's jacket in "Miss You." It clings to details, exposing them while contributing to the overall harmony of the composition. This thematic thread runs through the entirety of the artist's body of work.

Paradox

Jean-Baptiste Boyer's art exists in a captivating paradox, simultaneously timeless and firmly rooted in our contemporary era. This intriguing duality unfolds on canvas through a masterful balance of material, minimalist settings, the aesthetics of decay, the familiar dramaturgy of art history, and the chosen subjects.

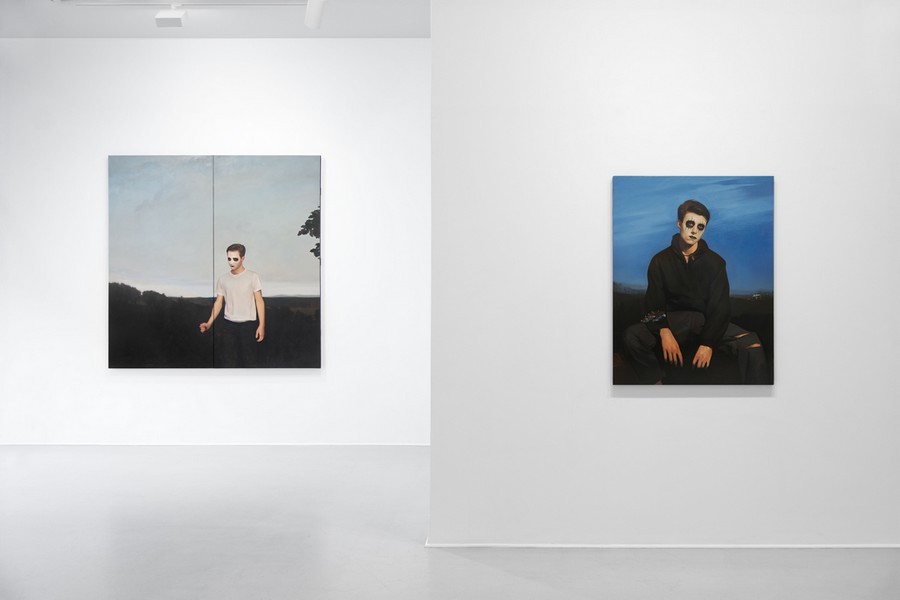

His subjects, depicted as solar and sensual young men, navigate the canvas—sometimes in solitude, immersed in introspection, or boldly exploring a fallen world with great curiosity. They are propelled by the desire to live, to revel in festivities, and to assert the freedom to "follow their demons," casting off societal and religious constraints. The words of Jean Starobinski resonate: "Fictitious prohibitions lead to imaginary indulgences," a sentiment vividly echoed in Boyer's painting, especially in the piece titled "Quel fardeau."

In this artwork, a young boy in immaculate trunks carries a staff topped with a cross just before a cave, poised for capture. He stands on the brink, threatened by the obscurantism that gnaws at society and minds—a resurgence of the repressed, if we adhere to psychoanalytical references. It's as if Jean-Baptiste Boyer is conveying that Eden can be experienced on earth, requiring only a few paradigm shifts and the breaking of societal locks. Beyond allusions to Piranesi or Hubert Robert, the ruins can be interpreted as the aftermath of a redemptive cataclysm, resetting the counters and inviting contemplation.

A Fantastic World

Enchantment, magic, and fantasy weave through Jean-Baptiste Boyer's creations, introducing mythical elements into the realm of reality. The satyr, traditionally linked with Dionysus, steps into our world, transforming the devil into a genial figure. The women portrayed in "The Baptism" could easily be mistaken for witches reveling in a Sabbath, guided by a particular joy. Within the confines of his paintings, temporalities condense, and disparate worlds converge.

As Jean-Baptiste Boyer elucidates, the genesis of all his work lies in emotions, and keen observers can discern the intricate construction of symbolic elements. Snails symbolize sexual freedom, skeletons signify vanity, caves represent obscurantism, rainbows embody harmony, and light embodies the inexorable passage of time. Certain motifs surface repeatedly throughout his body of work: the cross, the "clown" mask, and nudity. All of these elements unite in Boyer's exploration, a relentless quest for a particular kind of beauty.

Interview with Jean-Baptiste Boyer

What is the main theme of this exhibition at Galerie RX?

The year 2023 has been a year of significant upheaval for me, particularly marked by the loss of my dearly cherished dog. The exhibited series revolves around themes of melancholy, sadness, and the concept of mourning. Within this collection, several canvases bear titles that explicitly address the theme of lost love. For instance, "Lost Love" is depicted with neon letters on an abandoned merry-go-round, while "Heartbreak" portrays a hot-air balloon going down in flames.

My creative approach is not rooted in intellectualism but rather in sensitivity. I aim to capture and convey simple yet profound emotions through my paintings. If there is a single word that aptly defines my latest artworks, it would undoubtedly be "melancholy." These pieces serve as a poignant exploration of the emotional landscape shaped by the personal upheavals and losses experienced throughout the year.

Hence the importance of titles to give clues?

Yes, but the title comes after the fact, once the painting is finished. The real impetus is emotion. I imagine my paintings as films, with scenes that take shape in my mind and a soundtrack. I did a series in the abandoned Paris metro, and in the background, I pasted a poster of a music group that doesn't exist. In this way, each painting is a freeze-frame of a film I'm telling myself, with fictitious characters and music.

Does this refer to the music you listen to while painting?

I'm usually very concentrated when I paint, so I don't listen to music. Secondly, I'm a guitarist, and when I was younger I played for a while in an amateur band called Back on earth. It was a kind of punk rock band. I've kept that side of things, which I'd like to transpose into my painting.

In the exhibition, there are several abandoned places and a certain aesthetic of ruin. Do you make the connection with Piranesi or Hubert Robert?

Yes, Hubert Robert may have influenced my painting, but not exclusively. All it takes is for me to go for a walk somewhere and see moss growing on a staircase for it to suddenly evoke poetry and wonder in me, and thus material for my paintings. I draw my inspiration from both art history and everyday life.

In which world are you more comfortable? Today's world or the world of painting?

Today, I have the feeling that we are living in an upheaved world that's not very happy, and that sometimes society reverts to a form of obscurantism: what we take for granted isn't necessarily so, and religion is taking a place in society that it shouldn't have. That's why art is so important, because it enables us to portray serious or provocative issues with subtlety and nuance. Painting, which is vital for me, allows me to create another world in which I feel comfortable, even if it's sometimes very dark, and to bring out what I feel.

Are we close to romanticism then? When the landscape translates emotions.

Yes, it's true that the Romantic period inspires me enormously, with its fantasized landscapes that serve to accentuate a character's psychology. Both are treated on the same level.

What are your artistic references?

Delacroix is a painter I admire enormously for his vitality, his economy of means and his way of representing human beings. He interests me from start to finish. I could say the same about Goya, and to be a little different, I'd say that a lot of illustrators have nourished my practice. I don't come from the Beaux-Arts, but from the craft side of art, and I've always had a soft spot for illustrators with great technical skills. I'm thinking of John Howe and his illustrations of the Tolkien universe - the Fonds Hélène & Édouard Leclerc in Landerneau is devoting an exhibition to him until January 28, 2024. Even if it's a completely different style from mine, I think it's very beautiful. This imaginary world speaks to me and matches the unreal dimension that reigns in my paintings. It's a work of the imagination.

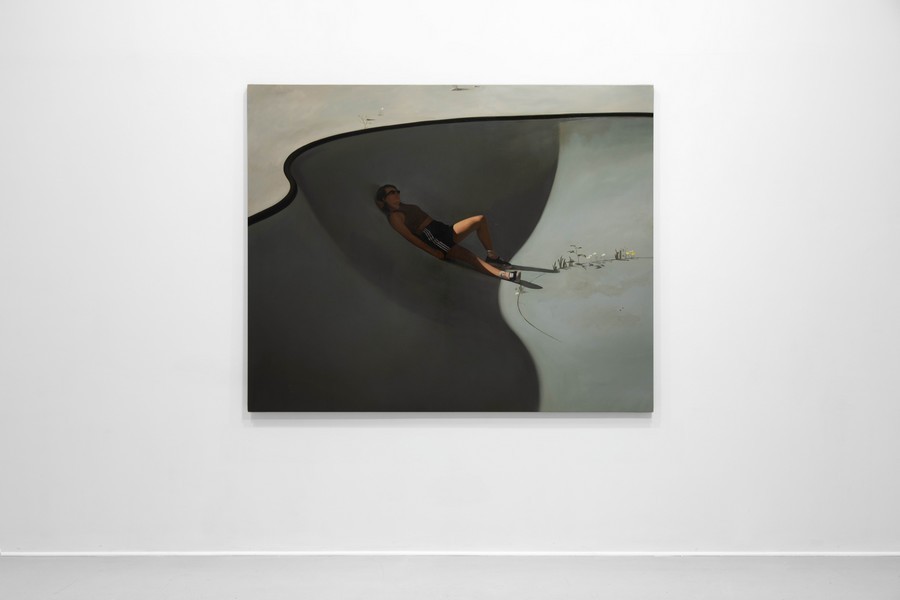

Fantasy is indeed part of the picture, as in Summercamp, where a satyr lies on the ground. What's wrong with his belly?

The ribs of this dead satyr stand out. The kids look at him as if they've discovered a fantastic creature, just as I imagined fantastic creatures in the forest when I was a kid. I wanted to reconnect with the marvelous side of life and the belief in slightly magical things. In another painting, a group of young people come across the remains of a lost civilization, human ruins.

In this rather dark world, there's Suivre ses démons. Is this an invitation to really follow one's demons or to fight against them?

I'd say it's more about following them! When I depict demons in my paintings, they're more like friends than enemies. When I was younger, I went to a private Catholic school where I took the liberty of emancipating myself from this ideological and religious straitjacket, and I find that following one's demons is a spark of madness and life. That scene with the kid on the devil's shoulders is like a middle finger to the world: you follow your path without religion or god, just being free.

What role does drawing play in your process?

It's very important! I have a sketchbook in which I make little sketches, and while I paint in oils for my canvases, in this case I work in gouache, a medium I like for its rapid, spontaneous quality. From my sketchbooks, I come up with themes and ideas, and sometimes I make drawings on tracing paper, which I superimpose to create compositions and scenes. Painting comes at the end of the upstream research process and represents only a third of the work.

So everything is very structured and you leave nothing to chance?

The fact that my compositions are very well constructed gives me a great deal of freedom to let myself paint. With very solid canvas foundations, I can follow my feeling and it's the touch that speaks.

In the course of your work, you seem to be focusing above all on capturing light. Is this the case?

Yes, light is important to me, and that's why I start with fairly dark backgrounds. I like the idea of sculpting light in my paintings, in the darkness of life, looking for that spark that emerges from the shadows, bringing that light to the fore to sublimate it. In these very dark atmospheres, it suddenly emerges!

Do you feel a sense of responsibility in what you do?

I have a responsibility to myself. I take art very seriously, and having the chance to present your work and sell it to collectors is very engaging. It's important to remain free to create, whatever the art, so I certainly don't censor myself. I'm not trying to provoke, just to get across what I feel, but if one day, for whatever reason, I were to offend someone with a painting, I wouldn't apologize. That's for sure.

What role does beauty play in your work?

I'd say I let myself be carried away by it, whether it comes naturally or not. If a painting is a success, it's because it contains a form of beauty. And if it doesn't, it's a failure....

Text by Stéphanie Pioda